Why is dairy booming and what does that mean for dairy farms and the industry’s sustainability?

Grow Well visited several dairy farms this past winter, an incredible learning experience that left me wondering more about the complexities, trends, and future of the dairy industry and what that means for its sustainability.

Got Milk?

Remember that catchy marketing campaign from the late ‘90s and early ‘00s, showing celebrities with those trademark milk mustaches? Advertising agency Goodby Silverstein & Partners first created the campaign for the California Milk Processor Board (CMPB) in 1993. The freshly formed dairy farmer-funded Dairy Management, Inc. (DMI) then licensed the campaign to go national in 1995 for ~$23M. Created to spur milk consumption, the campaign ran from 1993 to 2014 and then had a brief hiatus before being resuscitated and re-launched via social channels in 2020. Though DMI officially launched in 1995, dairy promotion has deep roots stretching all the way back to 1893 when California dairy farmers founded the Dairyman's Union of California. The official national forerunner of DMI formed in 1915 as the National Dairy Council as a primarily PR-focused organization tasked with repairing the industry’s image after a foot-and-mouth disease outbreak. Federally managed and mandated funding came in 1983, a congressional response to the 1980s Farm Crisis, that resulted in the formation of the National Dairy Promotion and Research Board. This was the beginning of the commodity checkoff model of mandated commodity research and promotion funding where producers pay a set fee per volume, value, or head of various commodities they may produce. Now there are more than 20 such programs covering everything from mangoes and highbush blueberries to beef, dairy, and soybeans.

Yet, despite all these years and all these dollars, U.S. per capita fluid milk consumption continued to fall, and is now down 50% over the last 50 years. How has the dairy industry survived and managed to create demand for something few people drink anymore?

Rapid Change

In 1975, milk production (all dairy products like fluid milk, cheese, yogurt, or ice cream) in the US was 115 million pounds (USDA Economic Research Service). Nearly 50 years later, in 2023, that figure stands at 226 million pounds of milk production, an increase of more than 96%. This is not because we have 96% more Americans or Americans have doubled their milk consumption. U.S. population has just increased a little over 50% in that time period, and per capita dairy product consumption only increased 20%.

So, the question is where is all this milk going?

Exports and everything but actual fluid milk.

While per capita milk consumption of all production in 2023 was 20% higher than in 1975, consumption of fluid beverage milk itself is down more than 48% in the same period. Consumer preferences have changed, and fluid milk has struggled to remain competitive in the market, despite the marketing campaign. Americans today consume their dairy in the form of concentrated products like cheese, butter, or yogurt (and increasingly Greek-style or concentrated forms of yogurt).

Cheese has seen a dramatic increase in the last few decades. Not only has per capita consumption of cheese products grown more than 50% since 1990, but Americans are now eating more than 40 pounds of cheese per person per year. While not the same in terms as cheese in terms of absolute consumption, yogurt has also seen a sizable increase in the rate of consumption, going from a niche snack product to a staple in households all over the country. Per capita consumption of yogurt increased 60% from 2003 to 2023, although this resulted in an increase of only 5.2 additional lbs. per person consumed (USDA ERS).

Unsurprisingly, this upward swing in yogurt and cheese consumption has come at a time when buyers are increasingly more conscious about their protein intake. According to Cargill’s 2025 Protein Profile, more than 60% of consumers increased their protein intake in 2024, a number that was only 48% in 2019. These non-fluid milk products represent a way for customers to satiate their protein cravings at a low price point relative to meat.

The other major demand driver is the popularity of GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic or Wegovy. These drugs have decreased chip or cookie sales for some companies, while increasing sales for major producers of dairy products. Rafael Acevedo, president of yogurt at Danone North America, claims that yogurt consumption is 3 times higher in US households that use GLP-1 drugs. Accordingly, Oikos (Danone’s protein-packed Greek yogurt) saw a 40% increase in retail sales in 2024. With the intake of GLP-1s only expected to climb in the coming years, yogurt manufacturers are well positioned to take advantage of this growing market.

While these growing concentrate markets are great for upstream food companies, the dairy farmers themselves experience more complex pricing and financial factors than other segments of the industry.

Price Sensitivity & Exports - Other key explainers of industry dynamics

Over 75% of U.S. milk production is overseen by the USDA’s Federal Milk Marketing Order (FMMO). The intent of the FMMO is ensuring that dairy farmers are paid the same price for their milk, regardless of what end product it is turned into (cheese, yogurt, fluid, etc.). The FMMO sets minimum prices that farmers must receive for their milk, by using varying price levels or classes, based on what end-use product that milk is being used for. Each class of product pays a percentage into a larger pool which is then used to compensate farmers of other classes. The four different classes that make up the FMMO program are:

Class I - fluid milk, with prices based on Class III & IV

Class II - soft dairy products like ice cream or yogurt, with prices based on non-fat dried milk (NFDM) and butter

Class III - hard cheese products, with prices based on cheese, whey, and butter

Class IV - butter and NFDM, with prices based on those products

Each class is interconnected, ensuring that the prices farmers receive are consistent throughout the market and relative to the amount of milk they are contributing to the different end products.

Class I products pay the most money, but with demand for those goods decreasing, farmers have had to look for other solutions. For many, this has meant consolidation, hoping that the economies of scale can offset some of the price stagnation present in the dairy industry. The number of dairy farmers has significantly decreased in the US, while herd size has gone in the other direction. Fifty years ago, there were nearly 500,000 individual dairy farmers across the country, today that number sits at under 30,000. There are just 27,000 dues-paying dairy farms contributing to DMI now. Recent amendments to the FMMO, passed on June 1st, have sought to calm this tide or at least give farmers more financial breathing room. The biggest update to the program has been changing the way Class I milk is priced. By considering the higher of the Class III or Class IV skim milk prices, instead of the average, fluid milk prices will be more enticing to producers. Higher prices for fluid milk will mean more farmers who are looking to sell their dairy into those products, instead of cheese or butter that offer less enticing profits. Class I products are also now considering the higher costs associated with selling fluid milk. The policy message is clear - the fluid milk market needs to pay farmers more. While the effectiveness of these price changes remains to be seen, the industry is clearly looking for ways to combat the over-supply of fluid milk in the US.

For years, producers focused primarily on maximizing milk volume production, a focus that shifted the national herd to nearly all cows of the highly productive Holstein breed. Now producers are shifting their focus to components - increasing production of fat and protein, not necessarily volume exclusively. This shift is motivated by consumers’ shifting consumption patterns away from fluid milk to butter, cheese, and Greek yogurt.

With such a massive amount of domestic supply, the dairy industry has increasingly had to look overseas to offload its product. The reality is that there is simply too much milk produced in this country, no matter how much demand for yogurt and cheese has grown in recent years. These concentrated products, along with items like whey or milk powder, hold up well in transport along international supply chains and have strong markets abroad. As a result, the US has begun exporting more and more milk -over 11 billion pounds in 2023. In 1990, this number was only 1.8 billion pounds, meaning that in only 25 years the dairy export industry has grown ten times over. The International Dairy Foods Association has claimed that this is a “golden age” for US dairy trade, referencing the over $8 billion of global exports that the industry saw last year. Most of this trade is occurring with Mexico, Canada, or a handful of smaller Central American markets.

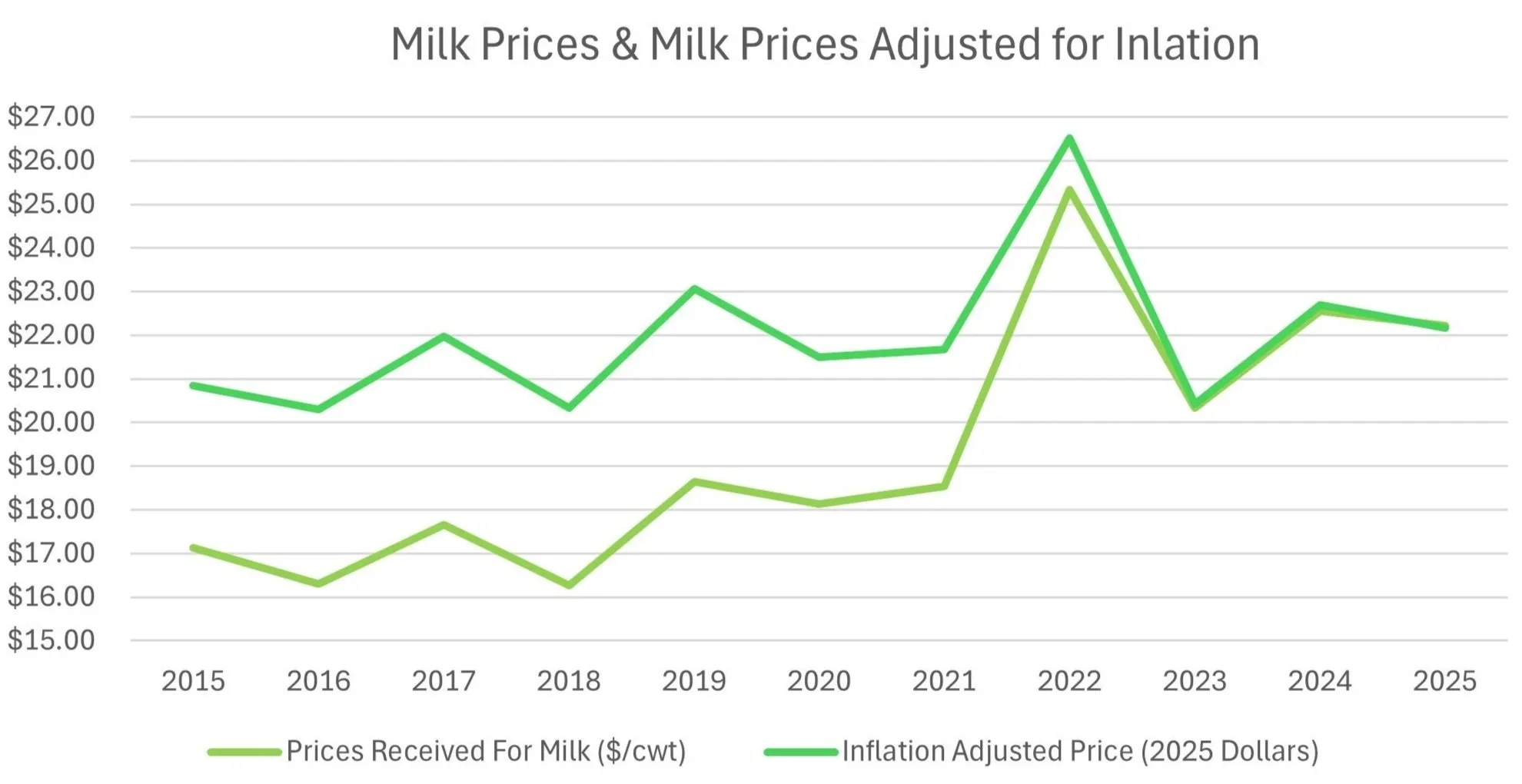

However, this surplus product also means the domestic price paid for milk has plummeted. According to the USDA ERS, a hundredweight (CWT or 100 pounds) of milk cost about $16.30 in 2016. In 2023, that number was only $20.50 – an absolute increase in price but not when considering the record inflation that consumers have experienced post-COVID. Accounting for that inflation, the price per cwt of milk has stagnated over the last 10 years, creating a significant pain point for farmers.

Relative vs. Absolute Emissions

Milk production has nearly doubled in the last 50 years. Improvements in efficiency, genetics, and animal care have made dairy cows much more productive on a per cow basis or per gallon of milk basis. Productivity is great for business, but what about the environmental impact of all this additional milk? More productive cows should mean fewer cows on farm and fewer cows on farm should mean fewer enteric emissions associated with the dairy industry. Yet that has not been the case.

While productivity has continued to increase over the last 30 years, the total number of milk cows remains almost exactly the same as what it was 30 years ago when DMI launched Got Milk - about 9.3-9.4 million cows. An increase in productivity paired with these high herd numbers has not only contributed to the over supply issues mentioned in previous sections but has also served to greatly increase the GHG emissions of the dairy sector.

This is where contextualing emissions data becomes important. Many in the dairy industry have been quick to claim that emissions have actually decreased significantly over the last several years. However, many of these claims are on a fat-and protein-corrected milk (FPCM) level - a way of standardizing milk across breed and production. With the exponential increases in milk production, it is not surprising the FPCM emissions have dropped, these are relative emissions values that do not take into account the absolute GHG emissions of the sector. Solely viewing emissions relative to productivity ignores the trends outlined above - dairy herd sizes have increased on a farm to farm basis and the number of total cows has not decreased. A recent landmark study headed by Dr. Alan Rotz and his USDA-ARS team supports this trend with quantitative data. While cow populations have declined somewhat along the East Coast, that has been balanced by increases in the western United States (the biggest dairy farm Grow Well visited was indeed in Idaho). Rotz writes on absolute emissions that, "The total emissions related to US dairy farms increased by 14% from about 88 Tg CO2e in 1971 to 100 Tg CO2e in 2020.”

Larger farms have forced farmers to switch their manure management systems away from more circular, solid storage models to liquid storage which increases methane emissions. Additionally, many of these farms now have more manure than land they can apply it to. The best way to lower absolute emissions is to store manure for short periods of time and spread as much as possible on croplands that will be harvested for feed. This creates a more sustainable model but one that is becoming less common on dairy farms. The official U.S. sectoral GHG inventory below shows emissions from manure management of dairy cattle have increased more than 80%, more than any other livestock sector.

While opting for more solid storage is a great way to stem emissions from manure management, optimizing heifer herd size and improving feed efficiency can help lower enteric emissions. The recent increase in productivity per animal has required significantly higher feed inputs. Researcher Sara Place hits on this trend writing, “Feed consumption is a key driver of CH4 emissions; thus, enteric CH4 emissions per cow in the US have increased. However, enteric CH4 emissions per unit of milk have declined as increases in CH4 emissions per cow have been offset by increased milk production.” Again, we see where the issue of relative emissions reporting can hide underlying factors. Farms can combat this by increasing the amount of feed grown on farms, buying in less feed, and spreading more manure on cropland to improve circularity. Grow Well witnessed this firsthand as well during our farm visits – the farms that managed manure through solid systems, on-farm application, and pasture-based systems, often had the lowest emissions.

A Boon for Western New York

At a time when tariffs and the political climate are driving manufacturing away from the US, the dairy industry has done the opposite. The increased demand for dairy products as well as the high supply levels of fluid milk have left many companies scrambling to keep up. As a result, there are a number of massive processing facilities currently being constructed. Alison and I actually learned about a few of these first hand through the dairy suppliers we met during our time in Western NY. Yogurt manufacturer Chobani has invested $1.2 billion to build its third dairy processing plant in the US, with the new site located in Rome, New York. At 1.4 million square feet, the facility will allow Chobani to grow its purchasing relationships with New York dairy farmers, as the company expects to increase its procurement of locally sourced milk by more than 500% once the site opens. Construction is also underway in the New York town of Webster, as fairlife and parent company Coca-Cola, have broken ground on a new milk processing facility that will handle more than 5 million pounds of milk per day.

For all the shifting consumer preferences, the dairy industry is still ideally situated. Decreases in GHG emissions have shown that there is potential for wide scale decreases across the industry, especially as cow productivity only continues to climb. Dairy producers also successfully weathered the oat milk storm, as that industry is now scrambling to reposition itself amidst lagging growth and shrinking earnings. Farmers will have to continue to navigate high input costs and stagnant retail prices but the growing export industry, skyrocketing cheese demand, and the uptick of domestic processing infrastructure provide plenty of reasons to be hopeful for the future. Adopting some systemic changes, like aerobic manure management and/or methane digestion and heifer herd size optimization, to reduce enteric and manure emissions can help ensure these trends improve the economic AND environmental sustainability of the dairy industry.

Cows managed on grass often produce lower volumes of milk with higher concentrations of fat, a benefit in a market focused on components with weak demand for fluid.